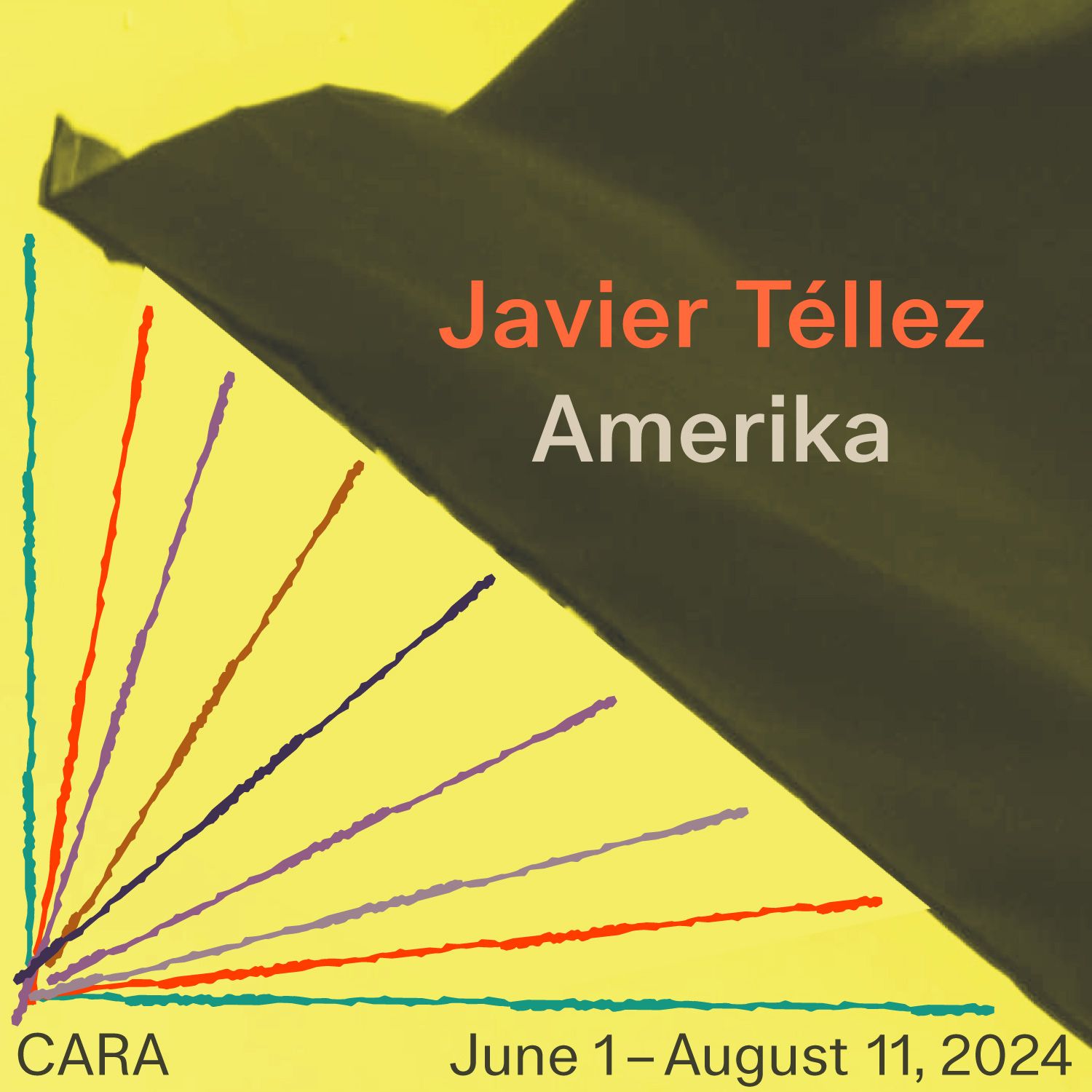

On Javier Téllez’s Amerika (2024)

For Téllez and his collaborators, experimenting with Chaplin’s films enabled expressive freedom.

Una versión en español del texto se puede encontrar aquí.

The films of Charlie Chaplin, some made over a century ago, would seem to have little to say to the political exigencies of today. Outwardly comedic and hyperbolic, they are more often programmed for children than taken up in spaces of serious, engaged art. Yet this is precisely what the New York-based, Venezuelan artist Javier Téllez has done with Amerika (2024), a short video work he made in collaboration with eight newly arrived immigrants to the United States, also from Venezuela: Andreina Arias, José Leoner Díaz López, Luisandra Escalona, Leonardo José Masa Mayora, Nazareth Merentes, Jesús Ramirez, Omar David Ríos Castellanos, and Mariana Vargas. Together they watched and discussed films, and, to the artist’s surprise, the group returned frequently to Chaplin.

As with Chaplin’s The Immigrant (1917), the individuals in the group had come from far away before arriving in New York. Many had crossed the treacherous Darién Gap between Colombia and Panama, before meeting Téllez at a shelter in New York. They, like the eight million people who have fled Venezuela in recent years, were seeking refuge from extreme poverty and political turmoil. The United States might have offered a fantasy of escape and, possibly, a better life. But as the reference to Franz Kafka in the work’s title suggests, it is also a nightmare, cold and often inhumane toward its newest arrivals. In this way, Téllez’s Amerika is a sidelong account of the present: the US border crisis told from the perspective of those who arrive, weary from a long journey, to find continued hardship and anti-immigrant hostility.

Amerika includes a credits sequence in which each participant states their name over an image of their identification cards. Beyond the bluntness of this Brechtian gesture, Téllez eschews conventional documentary form to tell the story of the actors. Instead of direct presentation, their concrete circumstances suffuse the project obliquely, through selected and modified scenes reenacted from Chaplin films. Collectively conceived by the group, the film describes the arrival of an outsider who accidentally gets caught up in a pro-immigration demonstration, is denounced as an agitator and thrown in jail, and is finally freed by his comrades. Téllez and his collaborators were especially drawn to Chaplin’s deeply humanistic and leftist vision, which included the brutal kettling of newly arrived migrants inThe Immigrant and the terrifying absurdity of the speeches in The Great Dictator (1940). Citing a scene from The Gold Rush (1925), in which a desperately hungry man imagines Chaplin is a chicken, the group decided to substitute a vulture; with food so scarce on the Darién, travelers there had taken to eating the bird of prey. Sometimes the Tramp himself appears: when the dictator’s cabinet has assembled to view footage of the protest, the 16mm projector on the table plays a scene from Modern Times (1936) in which Chaplin picks up a flag in the street, unaware of the striking workers massed behind him.

For Téllez and his collaborators, experimenting with Chaplin’s films enabled expressive freedom.Unburdened by the responsibility of “proper” representation of their circumstances, the group could then project themselves imaginatively into fictive spaces. By approaching their experiences indirectly, they were able to convey more than what a conventional retelling might allow. As Téllez described in an interview with CARA Senior Curator Rahul Gudipudi, “[t]hey are not talking about their experiences, they are talking about Chaplin. It's a bit like the iceberg image: you have the visible part and the invisible part.” What might otherwise be too painful to recount can remain indicated as the “invisible part,” the suggested depths beneath the surface of the image.

The actors play all the roles, both the Tramp and the underclass he represents, as well as their oppressors. This practice is born of Téllez’s childhood experiences of carnival in the psychiatric hospital where his father worked, in which patients and doctors would exchange roles. Play creates the possibility that an individual is not limited to a single role, as would be the case for an actor, but can don multiple, even contradictory ones. The effect of this interchangeability is profound. It reverses the course by which an individual becomes something less than a full person—a role, a statistic, a migrant bussed to New York City. It restores not just the humanity of the dehumanized, but their complexity. “We are not animals, we want work!” reads one of the film’s protest signs. The role reversals in Téllez’s casting, as well as his own authorial decentering, affirm a profound awareness of the many dimensions of the problem. The Tramp is also the dictator who pursues him, and vice versa. Community comes out of this deep sympathy.

Toward the beginning of the film, Téllez’s collaborators sit in a movie theater. It is plush and spacious—perhaps a nod to Téllez’s grandparents who ran one of Venezuela’s first movie theaters, Cine Capitol, in Turmero, Aragua State. As often happens in Téllez’s work, they watch themselves onscreen. Their eyes are bright and slight smiles appear on their faces. In addition to being actors, they are viewers. And in the gallery where Amerika played on a loop, Téllez had arranged eight cinema chairs in a row, one for each person, or for any visitor willing to occupy their seats for a while.

Genevieve Yue is an associate professor of Culture and Media and director of the Screen Studies program at Eugene Lang College, The New School. She is co-editor of the Cutaways book series at Fordham University Press, a member of the October advisory board, and an independent film programmer. Her essays and criticism have appeared in Reverse Shot, October, Grey Room, Film Comment, The Times Literary Supplement, and Film Quarterly. She is the author of Girl Head: Feminism and Film Materiality (2020).